Usage of the Heap Data Structure in Go (Golang), with Examples

Related Posts

So, Tell Me More About This Heap Data Structure

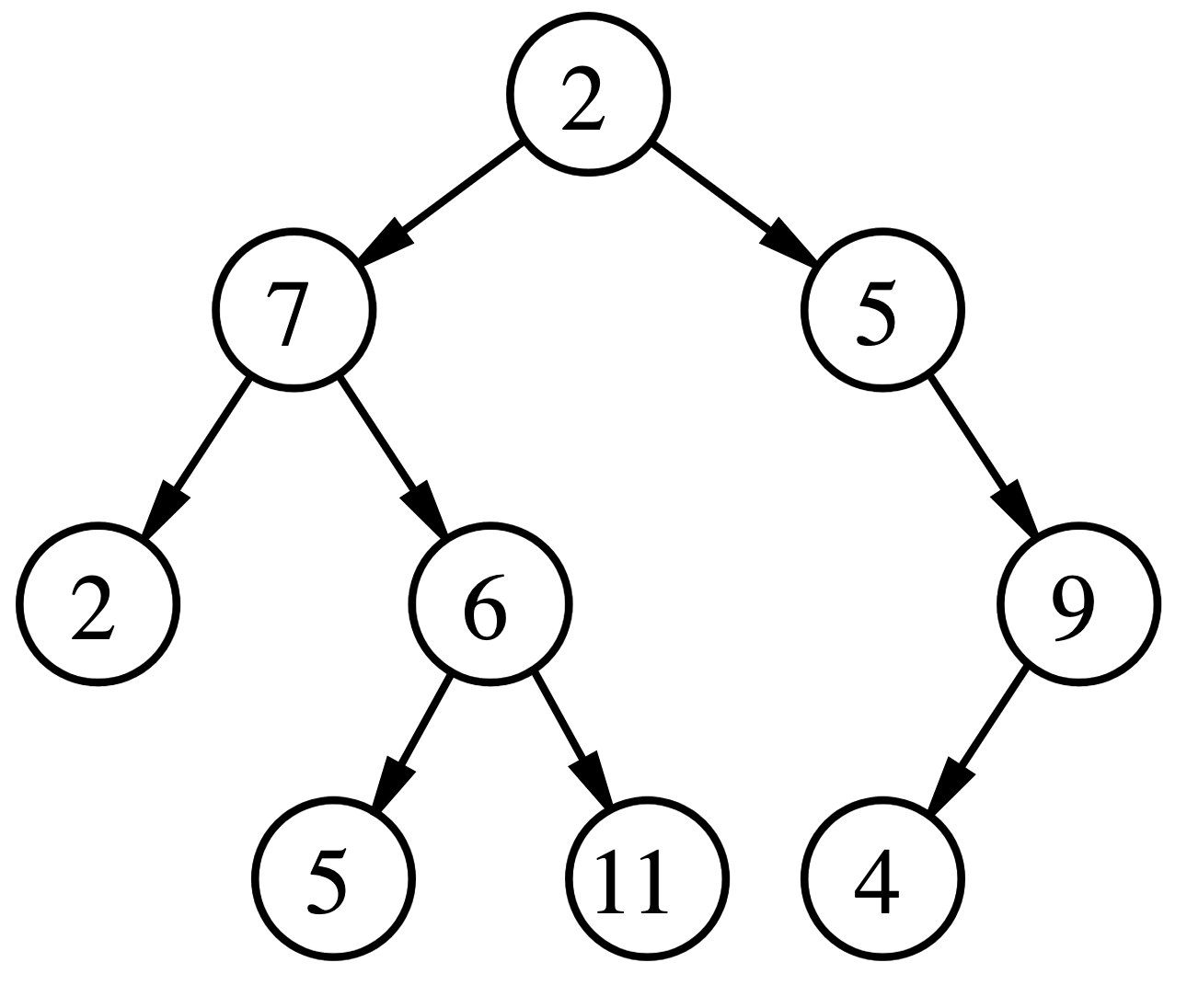

Heap is one of the most powerful data structures that is in our disposal to solve various real world problems more efficiently. Heap data structure usually comes with two shapes: Min Heap or Max Heap, and depending on which one it is, heap will give you efficient (i.e. O(1)) access to min/max value within the given collection.

Here is the characteristics of the heap data structure, which separate it from other data structure when all of these are combined together:

- a tree-based data structure, which is a complete binary tree

- In case of max heap, root node of the tree must represent the greatest value within the tree

- In case of min heap, root node of the tree must represent the smallest value within the tree

- Building a heap over an array of values has the cost of

O(n log n)in terms of time complexity (worst case), wherenis the length of the original array - Adding/removing a value from an existing heap has the cost of

O(log n)in terms of time complexity, wherenis the length of the heap

This information should be enough for us to get going for the purposes of this post, but if you want to understand a bit more on how to build a heap data structure, you can check this post out which shows some clever ways of building heap even with an array, instead of a tree.

heap Package in Go

Go is infamous for its lack of generics (which is hopefully changing soon), which makes it hard to implement this type of collection types very hard. That said, Go provides a package called container/heap which has heap operations for any type that implements heap.Interface.

heap.Interface has the below signature:

type Interface interface {

sort.Interface

Push(x interface{}) // add x as element Len()

Pop() interface{} // remove and return element Len() - 1.

}

As we can see, it embeds the sort.Interface into its signature. So, let's also see what that interface signature looks like:

type Interface interface {

// Len is the number of elements in the collection.

Len() int

// Less reports whether the element with

// index i should sort before the element with index j.

Less(i, j int) bool

// Swap swaps the elements with indexes i and j.

Swap(i, j int)

}

That's pretty much it. In a nutshell, Go asks us to implement some very basic operations on our own collection such as adding and removing a value, as well as requiring us to implement the sort interface which needs us to check which one of the given two values are less than the other, and doing a swap between two indices within the array. It also "kindly" asks us to perform some casting on behalf of it (ahem, covariance and contravariance, ahem, cough!).

There is still a catch here, since you can't add new methods to types outside package. For instance, the below code where we add methods to []int doesn't really work, with the error message of "Invalid receiver type '[]int' ('[]int' is an unnamed type)":

func (h []int) Push(x interface{}) {

*h = append(*h, x.(int))

}

We can get around this with a type declaration and attaching the method on that type:

type IntHeap []int

func (h *IntHeap) Push(x interface{}) {

*h = append(*h, x.(int))

}

You can swap the type int here with your own type, and build the heap structure for that type. For the purposes of this post though, we will continue with the IntHeap type which we have declared above. With that in mind, let's see how the final implementation looks like:

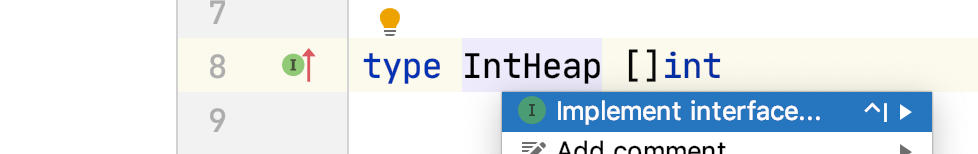

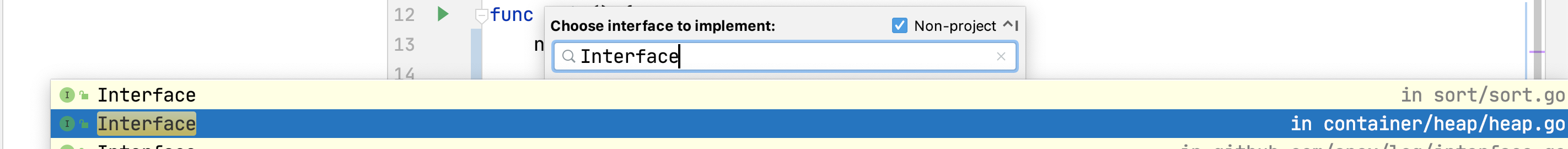

Tip 💡: if you are using Goland IDE, you can hit CMD + ENTER while your cursor is on the type, choose "Implement interface..." option, and then select the interface which you want to implement from the list, it will scaffold the structure of the interface for you:

type IntHeap []int

func (h IntHeap) Len() int {

return len(h)

}

func (h IntHeap) Less(i, j int) bool {

return h[i] < h[j]

}

func (h IntHeap) Swap(i, j int) {

h[i], h[j] = h[j], h[i]

}

func (h *IntHeap) Push(x interface{}) {

*h = append(*h, x.(int))

}

func (h *IntHeap) Pop() interface{} {

old := *h

n := len(old)

x := old[n-1]

*h = old[0:n-1]

return x

}

That's pretty much it. As you can see, all the implementation we had to do is for rudimentary operations, nothing fancy. We can now make use of this by initializing a variable with the given type: h := &IntHeap{}, and then start making use of the heap. functions. Below, you can see a very basic example where we build the heap from a set of values inside an array, and then start printing them (which is essentially the same as performing heap sort):

func main() {

nums := []int{3,2,20,5,3,1,2,5,6,9,10,4}

// initialize the heap data structure

h := &IntHeap{}

// add all the values to heap, O(n log n)

for _, val := range nums { // O(n)

heap.Push(h, val) // O(log n)

}

// print all the values from the heap

// which should be in ascending order

for i := 0; i < len(nums); i++ {

fmt.Printf("%d,", heap.Pop(h).(int))

}

}

The output is the values printed in ascending order, as you expect:

➜ git:(master) ✗ go run main.go 1,2,2,3,3,4,5,5,6,9,10,20,%

A Practical Application of Heap Data Structure

That's great, but what are the real world applications of this data structure? There are a few, and I want to focus on one real world example of this today: finding the k best elements within an unsorted array with the length of n, where the definition of "the best" is the largest value in the array. Seems straight forward! If we are after solving this problem by spending minimum effort, the easiest way is by basically sorting the array and returning the first k elements from it. The code for this would look like as below:

func FindBestKElementsWithSort(nums []int, k int) []int {

sort.Slice(nums, func(i, j int) bool { // O (n log n)

return nums[i] > nums[j]

})

return func() []int { // O (k)

result := make([]int, k)

for i := 0; i < k; i++ {

result[i] = nums[i]

}

return result

}()

}

We can also test it with the below code, to ensure that the logic works as expected:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"testing"

)

var bestElementsTestdata = []struct {

in []int

k int

f func(nums []int, k int) []int

out []int

}{

{[]int{3, 2, 1, 5, 6, 4}, 2, FindBestKElementsWithSort, []int{6,5}},

{[]int{3, 2, 3, 1, 2, 4, 5, 5, 6}, 4, FindBestKElementsWithSort, []int{6,5,5,4}},

}

func TestBestElementsLogic(t *testing.T) {

for _, tt := range kthElementTestdata {

t.Run(fmt.Sprintf("%v", tt.in), func(t *testing.T) {

out := tt.f(tt.in, tt.k)

if out != tt.out {

t.Errorf("got %q, want %q", out, tt.out)

}

})

}

}

The time complexity of this is going to be O (n log n + k), which is not bad. However, we can do better with the assumption that k will be smaller than n here. In a real world case, where we want to, for example, find the best top 100 results within a result set of millions, this assumption will be the key part to our optimization.

With that in mind, what we can do instead of directly sorting the array is to maintain a heap with the max length of k, and once we iterate over the entire given list, we can then reverse the result from our min heap. The code for this will look like as below:

func FindBestKElements(nums []int, k int) []int {

h := &IntHeap{}

for _, val := range nums { // O(N)

heap.Push(h, val) // O(log K)

if h.Len() > k {

heap.Pop(h) // O(log K)

}

}

return func() []int { // O (k log k)

result := make([]int, h.Len())

initialLen := h.Len()

for i := initialLen; i > 0; i-- {

result[i-1] = heap.Pop(h).(int)

}

return result

}()

}

We can now extend the original test cases to make sure that our logic works as expected:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"testing"

)

var bestElementsTestdata = []struct {

in []int

k int

f func(nums []int, k int) []int

out []int

}{

{[]int{3, 2, 1, 5, 6, 4}, 2, FindBestKElements, []int{6,5}},

{[]int{3, 2, 3, 1, 2, 4, 5, 5, 6}, 4, FindBestKElements, []int{6,5,5,4}},

{[]int{3, 2, 1, 5, 6, 4}, 2, FindBestKElementsWithSort, []int{6,5}},

{[]int{3, 2, 3, 1, 2, 4, 5, 5, 6}, 4, FindBestKElementsWithSort, []int{6,5,5,4}},

}

func TestBestElementsLogic(t *testing.T) {

for _, tt := range kthElementTestdata {

t.Run(fmt.Sprintf("%v", tt.in), func(t *testing.T) {

out := tt.f(tt.in, tt.k)

if out != tt.out {

t.Errorf("got %q, want %q", out, tt.out)

}

})

}

}

Result:

➜ git:(master) ✗ go test --run=TestBestElementsLogic -v

=== RUN TestBestElementsLogic

=== RUN TestBestElementsLogic/[3_2_1_5_6_4]

=== RUN TestBestElementsLogic/[3_2_3_1_2_4_5_5_6]

=== RUN TestBestElementsLogic/[3_2_1_5_6_4]#01

=== RUN TestBestElementsLogic/[3_2_3_1_2_4_5_5_6]#01

--- PASS: TestBestElementsLogic (0.00s)

--- PASS: TestBestElementsLogic/[3_2_1_5_6_4] (0.00s)

--- PASS: TestBestElementsLogic/[3_2_3_1_2_4_5_5_6] (0.00s)

--- PASS: TestBestElementsLogic/[3_2_1_5_6_4]#01 (0.00s)

--- PASS: TestBestElementsLogic/[3_2_3_1_2_4_5_5_6]#01 (0.00s)

PASS

ok _/Users/tugberkugurlu/go/src/github.com/tugberkugurlu/algos-go/kth-largest 0.835s

The time complexity of this is O(n log k + k log k), which is much better.

Benchmarking

But, how much better? To be able to understand the improvement we have made here, we can run a benchmark between the two implementations with Go's built-in benchmark tooling. For this, we will go with the below benchmark setup:

- Random input of an array with 10M items

- We will use the same set of input across all the runs to be able to make the comparison fair. We will achieve this by using the

TestMainhook in Go. - Value of

kas 500 - For each run, we will make a copy of the array so that we can run the benchmark deterministically since the sort based solution mutates the given array, and we will also do this for the heap based solution to make the comparison fair

package main

import (

"math/rand"

"reflect"

"testing"

)

var nums []int

func TestMain(m *testing.M) {

maxVal := 10000000

nums = make([]int, maxVal)

for i := 0; i < len(nums); i++ {

nums[i] = rand.Intn(maxVal)

}

m.Run()

}

func BenchmarkFindBestKElementsK500(b *testing.B) {

k := 500

for n := 0; n < b.N; n++ {

nums2 := make([]int, len(nums))

for i, v := range nums {

nums2[i] = v

}

FindBestKElements(nums2, k)

}

}

func BenchmarkFindBestKElementsWithSortK500(b *testing.B) {

k := 500

for n := 0; n < b.N; n++ {

nums2 := make([]int, len(nums))

for i, v := range nums {

nums2[i] = v

}

FindBestKElementsWithSort(nums2, k)

}

}

We can run this benchmark with go test command. However, note that the exact time that takes to run each function is not significant here, since it will depend on the machine spec, etc. Also, in the test, we are copying the input array for each run, which means extra time we are adding to the exact time to run the function. That said, what's important to observe here is the difference in time between two functions:

➜ git:(master) ✗ go test -bench=BenchmarkFindBestKElements -benchtime=30s goos: darwin goarch: amd64 BenchmarkFindBestKElementsK500-4 15 2200446151 ns/op BenchmarkFindBestKElementsWithSortK500-4 13 2618637516 ns/op PASS ok _/Users/tugberkugurlu/go/src/github.com/tugberkugurlu/algos-go/kth-largest 72.740sThe heap based implementation is about 20% faster than the sort based implementation, which is a significant difference of performance. More importantly, this diff will get worst as the length of the array increases.

Conclusion

Heap is a powerful data structure, which is a perfect to solve some real world problems most efficiently. However, it's often overlooked. Hopefully, this post sheds some light on where this data structure can be useful for us in terms of efficiency, and how Go programming language helps us by providing the necessary ground work to work with data structure even if it's still not at the desirable level in terms of reusability due to lack of generics in the platform (which means that I used all my daily allowance for ranting about lack of generics in Go).